Why the Right and the Left have to Rethink

Understanding politics according to the old divide no longer makes sense.

Let’s see if we can find something we agree on.

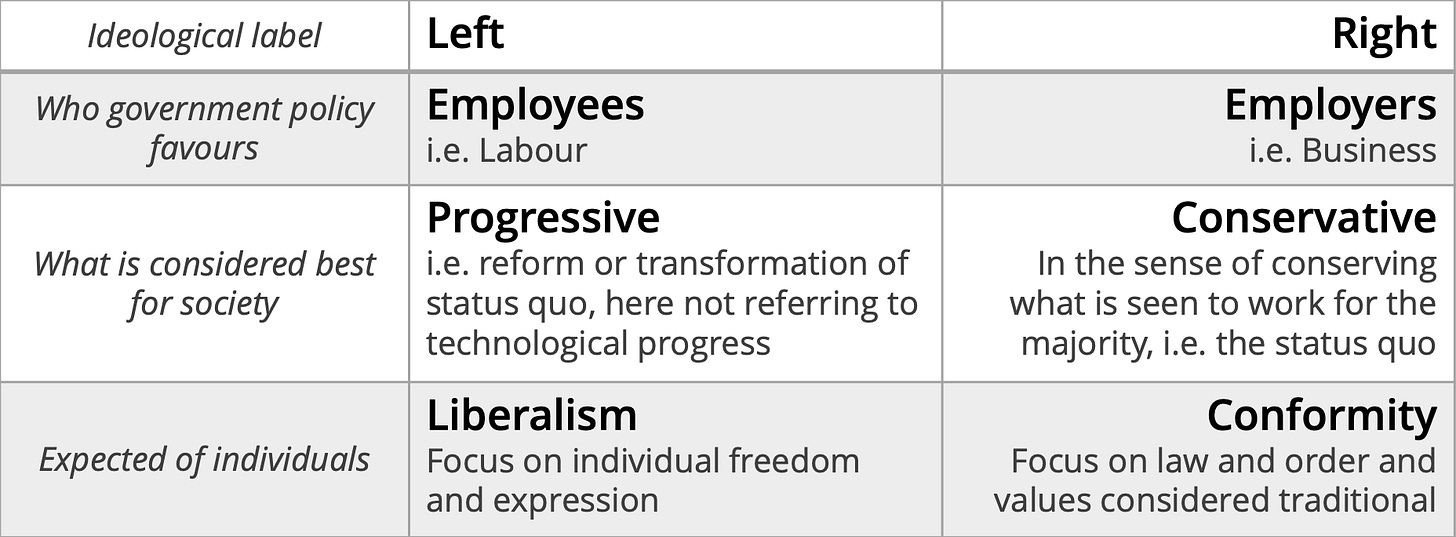

On the oft-mentioned left-right political spectrum, ‘right’ traditionally refers to conservative ideas of how a society should be run, whereas ‘left’ is associated with the interests of the labouring classes, or working people, meaning employed people.

Is that a fair summary? Can we all agree on that?

However, as conservatives see it, making sure the economy is working well – i.e. by promoting the interests of business – is ultimately in everyone’s interest. Because only when businesses are successful are they able to employ people. So the ‘right’ claims to be acting to benefit working people too.

So how about we put it like this: The ‘left’ is associated with the direct interests of the labouring classes and the ‘right’ with business interests, though the idea of the ‘right’ is that if business flourishes, so does labour.

Are we still agreed?

How about: ‘Left’ is often associated with ‘progressive’ ideas of how to achieve the better organisation of society. ‘Progressive’ stands for reform or even transformation. ‘Progressives’ think the status quo needs to be adapted and improved. They have ideas for changing the way things are organised so that society works more fairly.

And what is the counterpart of ‘progressive’? No political party thinks of itself as regressive. It’s more a matter of the non-progressives wanting to keep things as they are. There’s a feeling of certainty to the current setup and uncertainty if you changed it too much. These people want to conserve the status quo, because they think the status quo is fair enough. So the opposite of ‘progressive’ is ‘conservative’.

Can we agree this far? I haven’t upset anyone yet? I’m trying to be neutral and matter-of-fact here.

I find it interesting that the term ‘progressive’ comes from ‘progress’. Normally, we associate the term ‘progress’ with the advancement of civilisation. We have progressed from the stone age through bronze and industrial ages to the digital age. In general, progress seems to be associated with technological advancement and also with better living conditions. Nobody wants to go back to the middle ages, after all. And by measurable standards such as human life expectancy, child mortality rates, or wealth/poverty indices, there seems to be a correlation between technological progress and standard of living.1

But the political sense of ‘progressive’ does not necessarily correspond to technological progress. Many ‘progressives’ are wary of the rapid changes in society due to technological innovation, considering for instance AI (artificial intelligence) as potentially dangerous for human well-being.

On the other hand ‘conservatives’, since they are interested in promoting business, therefore promote the interests of investors, because investment is necessary for the growth of more business. And investors are very interested in technological progress. In fact, they look actively for ‘disruptive’ technologies to invest in, because when an industry is disrupted (as Uber disrupted the taxi business and Airbnb the hotel business), it promises greater ROI (return on investment) for the investors. Disruptive technologies are big business, and therefore what ‘conservatives’ like.

Disruption is, of course, the opposite of conserving the status quo. Nonetheless, it seems that when it comes to investment in technologies, ‘conservatives’ like to promote disruption and ‘progressives’ may be leery of progress.

So far we have been looking at how different people think the society should be run, that is organised or governed.

But a society is composed of individuals. The ‘left-right’ spectrum encompasses attitudes to how individuals should fit in to society.

People perceived as being ‘on the left’ are sometimes referred to as ‘liberal’. The word ‘liberal’ comes from liberty, which is another word for freedom, which most people in the western world think of as a good thing. So it is ironic that for some detractors, usually ones sympathising with the ‘right’ end of the spectrum, ‘liberal’ is almost an insult. As if some people are too free – free with their morals, perhaps, as in libertines.

So what is the counterpart of ‘liberal’?

Perhaps the non-liberal can be summed up as someone who is more traditionalistic. Someone who conforms to perceived established norms in society. Someone who values order and adherence to certain principles, such as moral standards and the rule of law. Would this be fair to say? It’s harder to put a tag on this person – unlike the ‘bleeding-heart liberal’.

Have I offended your political sensibilities yet? Or are we still on the same page? I’m trying not to take sides here.

I’ve spoken of advancement and I’ve spoken of individuals. What about the attitude towards individual advancement? That is, social mobility. In most western countries, both people on the ‘left’ and people on the ‘right’ think that it is desirable to better one’s social standing, which more or less equates to a higher income.

Some people believe that hard work pays off, and conversely that success is the result of either hard work or cleverness or both. So if an individual accumulates wealth or power, that shows they are simply better at doing so than the people who didn’t pull it off. This is the idea of meritocracy: society rewards ability, and leadership or belonging to an elite is the result of talent and ability. In general, ‘conservatives’ seem to think this is the way society works, whereas people on the ‘left’ tend to point out that the ‘playing field’ is not ‘level’, i.e. that some successful people became that with a head-start, by being born into more privileged families or environments. The poor have less chances for success than the rich, the ‘left’ say, especially if the particular poor also happen to belong to ‘minorities’. The ‘left’ might point to the injustice or indeed danger to society of too much concentration of capital and power in the hands of a few individuals.

It’s hard to find suitable tags to describe these diverging attitudes. I am loth to use words like ‘equality’ or ‘equity’ or to speak of ‘equal opportunities’ or ‘equal rights’, let alone ‘inclusion’, since these by now are such loaded and contentious terms. People get their hackles up quickly, and I’m trying to avoid that here. Would it be fair to call the one as having an ‘egalitarian’ focus and the other as being focused on individual merits?

Getting difficult to remain neutral, isn’t it?

There’s one more dimension of the ‘left-right’ spectrum I want to pick out, and that is the attitude to markets. The ‘right’ believe that society’s advancement hinges on economic growth, so the ‘right’ loves markets. Since the Scottish economist Adam Smith talked about the ‘invisible hand’ in the 18th century as creating order in markets, the ‘right’ preaches that markets should in general be left alone if they are to function most efficiently. The ‘left’, on the other hand, thinks that markets without control mechanisms create conditions favourable to big players but many smaller players are thereby pushed out. So completely free markets tend to favour the few and not the many (making them undemocratic, really). The ‘left’ often think people or some segments of civilisation need to be protected from market forces, because market forces are not always benign. In particular, fields such as education or healthcare or utilities such as waterworks or public transport need to have some degree of cushioning from decisions based purely on economic efficiency, in order to make sure that all members of society, including the poor or minorities, have access to life-essential services.

Businesses, the ‘right’ say, are more efficient than state-run or ‘public’ enterprises. Put simply, the ‘left’ prefer to regulate markets, whereas the ‘right’ prefer to de-regulate and privatise.

The term that sums up the ideas of the ‘right’ concerning markets is ‘neo-liberal’ – not to be confused with ‘liberal’, which – as we have seen – refers to people in the opposing camp.

I’m sure there are more dimensions we could talk about. For instance, how socialism connotes something completely different in Europe than in America. Or how communism and fascism are seen as a dichotomy although they are not – Stalin and Hitler as outstanding exemplars of each notwithstanding. Not to mention all the issues on which the ‘left’ and ‘right’ are supposedly divided, such as ‘migration’.

If you are not fuming yet, on your high horse berating me from afar, then perhaps you more or less in general basically agree with my efforts at sorting out some of the distinctions between ‘left’ and ‘right’.

But now comes the tricky part.

We summarised earlier that ‘progressives’ want to change things for the better whereas ‘conservatives’ prefer to conserve the status quo. ‘Conservatives’ think the status quo is safe. The system seems to be causing advancement and with it a higher standard of living for most people, so changing it bears a big risk. Change is seen as dangerous, in particular if it is unclear what to change to.

Now, in the year 2025, we have the situation that one of the biggest and most powerful nations on Earth is changing the global status quo. The Musk/Trump administration in the USA flagrantly disregards long-held constitutional norms. More than that, it is actively dismantling the civil service. The DOGE (‘Department of Government Efficiency’) under ‘rogue general’ Musk is purging all sorts of institutions, such as the FBI and CIA, of staff that may not be loyal to Trump, while Trump is installing loyalists in high positions in such institutions, as he has already done in the supreme court. Musk’s DOGE has also taken over the US government’s payment system, thereby gaining control over payments and access to private and sensitive information of thousands, neigh millions of individuals and organisations, and potentially compromising national security. Furthermore, many of the highly public executive orders that Trump signed in his first days in office appear to be illegal – so many that there is speculation that the plan was that the legal system gets clogged with law suits from opponents. The new administration was perhaps not only expecting this reaction but actually welcomes the inundation. Trump, himself guilty of 34 felonies, immediately upon becoming president pardoned hundreds of incarcerated felons, mostly the ones who stormed the capitol building in Washington on January 6th, 2021. So ‘rule of law’ does not seem to be a value that the new administration cares much about.

Not only is the new administration’s domestic policy violating established norms and disregarding the rule of law. So is the new US foreign policy completely overturning the worldwide order or status quo established after WW2. The Trump administration stopped the US government’s global humanitarian program USAID (United States Agency for International Development). This institution obviously did more than humanitarian deeds – it established and consolidated the US as a power in many poorer regions of the world. Without it, global players such as China are likely to rush in to fill the vacuum. The stopping of USAID actually has domestic consequences too because USAID used to buy millions of dollars worth of goods from US farmers for distribution abroad. The US has also left the Paris Climate Accords. And now the US is alienating former allies by claiming to want to make a deal with Russia’s leader Putin about Ukraine – without the participation of Ukraine itself or Europe. Actually, by weakening the civil service as well as upsetting it’s allies, Trump’s administration is definitely in a weaker position to negotiate a deal with Putin than before, even if the US had any right to do so.2

So the change ‘conservatives’ feared has not come from the ‘left’. It has come from the ostensibly conservative Republican party, or more specifically that powerful right-wing part of it known as MAGA (Make America Great Again).

The last 10 or 20 years saw the growth in power in the USA of the populist Trump and the pushing to the ‘right’ of a more or less middling party (remember the days of ‘bipartisan consent’, when in general the Democrats and Republicans agreed on all essential policy and merely fought about the details). This ‘populism’ is echoed in many other countries, where right-wing populists have gained much power and caused much change, such as Farage’s UKIP (who had a lot to do with the popular vote for Brexit) and Reform UK in the UK, Le Pen and National Rally in France, or the AfD in Germany. There is no reason to think that if they were installed in power in their countries as successfully as Trump is installed in his, that these right-wing populists would not try to dismantle the democratic system from within according to similar blueprints.

So conservatives have to be aware that if they want to conserve the system which apparently worked for them for many decades, they must avoid voting for these spuriously ‘conservative’ right-wing parties. Because these do not want to conserve the status quo. They want to destroy it.

By all appearances the replacements these right-wing parties offer are authoritarian systems. These centrally controlled regimes by definition give less freedom to their citizens. Conservatives beware! You won’t be able to choose to conform. You will be forced to conform. There’s a big difference.

For ‘progressives’, the situation is even more unnatural. They now find themselves in a position where the institutions and systems they criticised previously are infinitely preferably to having these institutions dismantled by a state that seems to be heading directly towards centralised authoritarian control. What needed reform or change or perhaps even replacement, now needs to be conserved, because without it the progressives fear dictatorship. Progressives are forced to be conservative!

So, you still agree with me? Or have I got it all wrong?

In fact, some of these standards are showing alarming signs of trend reversal. According to multiple sources such as the WHO or Harvard, human life expectancy is shortening now. Child mortality is still an issue. Poverty is not under control. So continuous progress towards a higher standard of living is by no means a given. See for example:

https://www.health.harvard.edu/blog/why-life-expectancy-in-the-us-is-falling-202210202835

https://www.who.int/data/gho/data/themes/mortality-and-global-health-estimates/ghe-life-expectancy-and-healthy-life-expectancy

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9462908/

https://www.who.int/news/item/20-12-2021-latest-child-mortality-estimates-reveal-world-remains-off-track-to-meeting-sustainable-development-goals

https://www.vcuhealth.org/news/rising-child-mortality-in-the-us-has-the-most-impact-on-black-and-native-american-youth/

https://sdg.iisd.org/news/global-extreme-poverty-back-to-pre-pandemic-levels-world-bank/

https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-023-02098-3

https://ourworldindata.org/poverty

All of my statements in the above two paragraphs have been documented and reported, though it is surprising how little the waves are that these unprecedented changes are making. Probably the best ongoing summary of what is currently going on in the US is historian Heather Cox Richardson’s substack Letters from an American:

Also commenting insightfully on these developments is another historian and author, Timothy Snyder, in his substack Thinking about...: